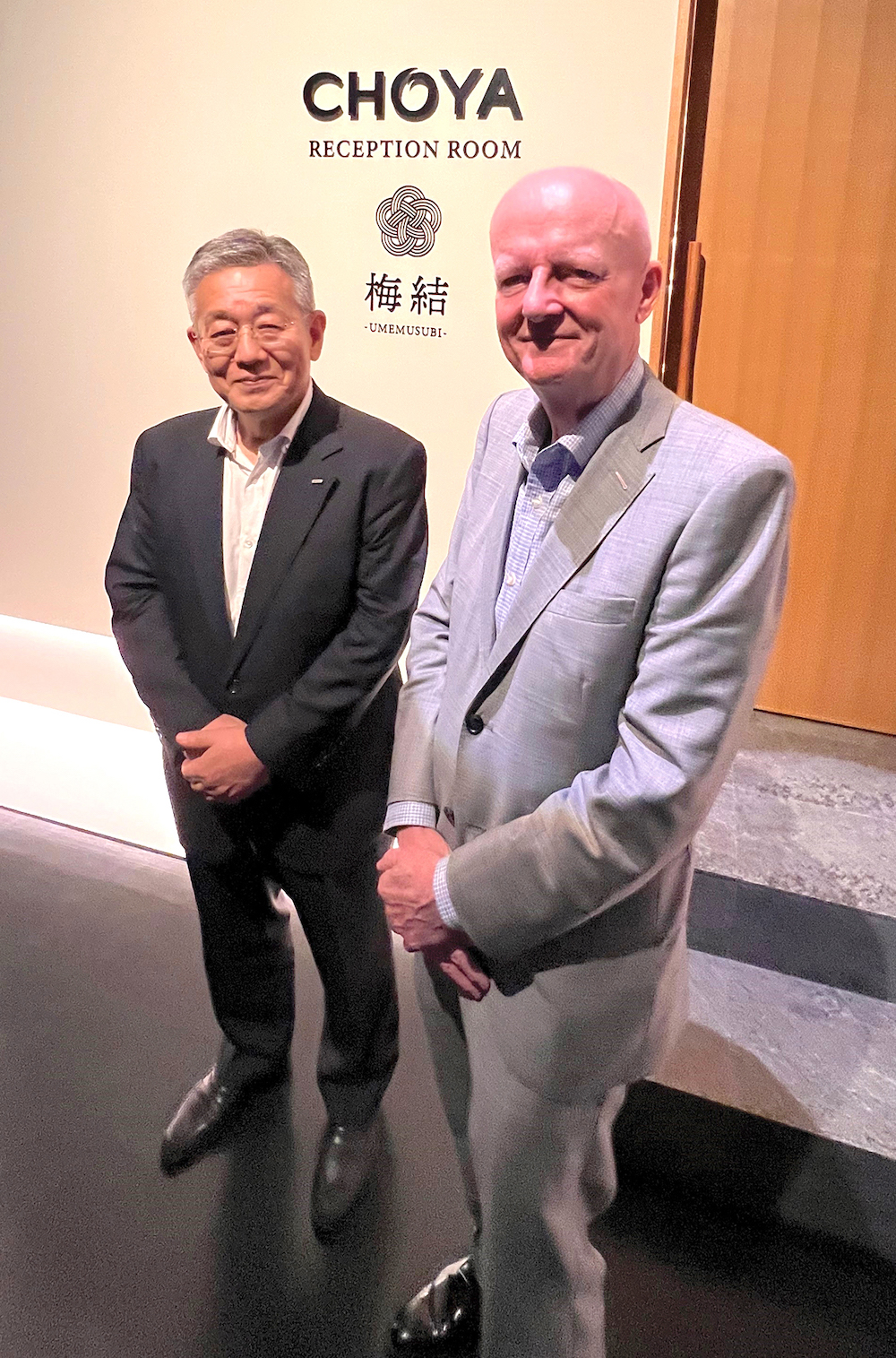

Choya is one of the great yet arguably unsung success stories of the global drinks industry and a familiar sight on the shelves of many Asia Pacific duty free stores. The hugely popular Umeshu brand is a particular hit in the channel not only with Japanese consumers but also with Chinese travellers and a growing band of international aficionados. Martin Moodie visited Choya headquarters in Osaka to learn more about this renowned Japanese fruit liqueur and catch up with CEO Shigehiro Kondo.

Shigehiro Kondo is the proud third-generation flagbearer for Choya, Japan’s premiere Umeshu producer, a unique Japanese liqueur made from a blend of Ume fruit, shochu and alcohol. The group was founded by his grandfather Sumitaro Kondo in 1914 as a grape winemaker and brandy producer, a sector that sustained the company for 45 years until 1959 when the family made the seminal decision to diversify into Umeshu production.

“My granddad retired when he was 60 years old and started travelling overseas,” recalls Shigehiro Kondo, talking during a tutored tasting of Choya expressions at the company headquarters in Habikino, Osaka Prefecture.

“When he visited Bordeaux and Burgundy in France he discovered fine wines of much higher quality than his own that were available at prices lower than his own costs. In those times, French wine was only available in Japan on quota so the price was very high. But he knew that once imports were liberalised, he simply couldn’t be competitive here. It was a worrying time.”

But like the grapes he grew, Sumitaro Kondo’s roots lay in the Japanese soil. Instead of taking the easier option of promoting imported products, he dreamed of nurturing a tradition that was unique to Japan, eventually hoping to share it with the rest of the world.

“So he passed his job to his three sons and that’s when he and they decided to start this traditional Umeshu business,” explains Shigehiro Kondo. “We were one of the pioneers in commercialising this product.” Leaning on its agricultural heritage, the nascent Umeshu producer set out on a mission to create an outstanding and consistent product by developing ‘hand in hand’ with local Ume growers.

The brand they created took its name from the combination of a Japanese butterfly species called the Gifu Chō found in the Komagatani area near the company’s headquarters and artefacts from the Stone Age shaped like arrowheads (called ‘ya’ in Japanese) also found there. The dual honouring of nature and the local community – a key mantra ever since – became the combination of the two. Choya was born.

Six and a half decades on, Choya ranks as a great Japanese success story. But like so many entrepreneurial journeys the going was not always easy. In 1962, the Kondo family incorporated the company under the name Choya Yoshu Jozo (Brewery) Co., but commercial progress was painfully slow with many liquor stores reluctant to list a product that until then was only made (illicitly until 1962) by Japanese families at home.

But amid societal changes in the mid-1970s led by increasing urbanisation, demand for commercially produced Umeshu steadily increased. As domestic sales grew, Choya’s eyes turned offshore. The company began exporting in 1968 and in the mid-1980s entered Europe, hosting regular tastings to introduce Western audiences to the unfamiliar liqueur. In 1990, Choya established a subsidiary in Germany, a seminal moment in realising Sumitaro Kondo’s dream of taking the spirit of Japan to the world.

Beware of cheap imitations

Through the 1990s the Umeshu sector really took off as young people started enjoying the beverage. By 1994, the category was showing a fivefold increase over the previous decade, continuing to rocket in the ensuing years. Choya opened subsidiaries in China and the US, underlining Choya’s escalating success. In 2000, the company changed its corporate name to Choya Umeshu Co., reflecting its specialisation in Umeshu production.

But success inevitably brings imitators. As the Umeshu market expanded through the 21st century, products made with artificial additives instead of real Ume fruit began to crowd the market, endangering not only Umeshu’s reputation but farmers’ livelihoods. In response, Choya helped drive the creation of a category called Honkaku Umeshu (Authentic Umeshu) in January 2015 so customers knew if they were drinking the genuine article.

From that point only Umeshu made with the traditional manufacturing method – using solely Ume fruit, sugar and alcohol – could be called Honkaku Umeshu. The following year ‘The Choya’ was born as a Honkaku Umeshu series of expressions, now found in many duty free stores at home and abroad.

Today Choya is the country’s leading Umeshu brand, despite big-budget competition from drinks sector giants Suntory and Kirin. Key international markets include China, the US, Germany and a very strong travel retail presence.

“I think we have done a good job so far but we have a new target,” says Kondo of the company’s progress. That goal is for consumers to think only of The Choya when they consider Umeshu (the use of ‘The’ before Choya is a definitive statement to that effect), a case of a brand transcending a category.

Travel retail’s vital role

I ask how successful the company has been in communicating that status to overseas consumers in particular. “It is partially realised, especially among Chinese,” he responds. “So Chinese people don’t talk about the Umeshu category, they say ‘The Choya’. But we want to deepen that brand awareness to other nationalities.”

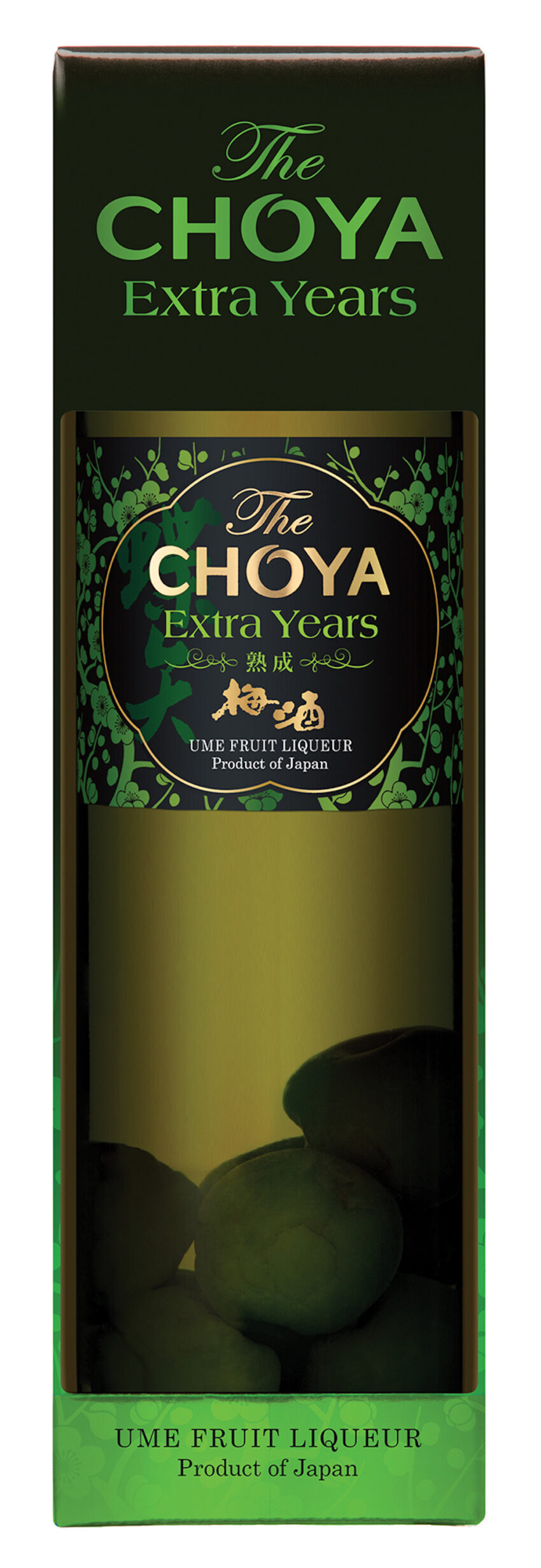

Travel retail plays a key role in pursuing that aim. Walk into the wines & spirits departments of many duty free stores around Asia Pacific and it’s almost impossible to miss The Choya range of Ume fruit liqueurs, many tantalizingly displaying bobbles of the small Ume fruit inside the bottles.

Kondo is deeply committed to travel retail, especially given that the channel allows The Choya to present itself as an attractive brand in its own right rather than as part of the wider Umeshu category.

Travel retail offers an ideal opportunity to embed the brand’s identity in the minds of travellers, serving as an international showcase as well as a pure sales channel, he points out.

Travel retail has helped build Choya an increasingly healthy balance between the Japanese market (70%) and offshore business (30%), the latter being led by Greater China, followed by the US and selected European countries. While the brand is predominantly strong in the off-trade in Japan, it enjoys a healthy on-trade presence in Germany due largely to Choya’s popularity in Chinese restaurants.

Though the prolonged COVID-related constraints hit Choya along with all its peers, Kondo says the 2023 performance has been encouraging and short to mid-term prospects look good. Sales are almost back to pre-pandemic 2019 levels and he is confident of strong growth next year.

Quality control at its highestA visit to the Choya Iga Uneo factory offers an enthralling view into this most traditional of Japanese products and the craft and dedication that underpins it. Under the expert guidance of Choya Master Blender Masahiro Iida and accompanied by Choya General Manager Masahiko Kondo and Choya Overseas Department Deputy General Manager Seiji Susuki, I learn how thousands of Nanko Ume fruit are blended with shochu spirit and sugar, then aged in giant storage tanks with no artificial additives. The 8-metre-high tanks, capable of holding 100,000 litres, protect against external influences such as light, temperature and air, allowing the blended liqueur to age untouched (Still Ageing) for more than a year to fully extract the Ume character. The careful maceration of the high-quality fruit generates The Choya’s trademark rich flavours balanced by natural organic acids. By using an unusually large number of high-quality Ume fruit, the generous flavours are fully drawn out along with other Ume components such as organic acids, which are gentle on the body. A single bottle of The Choya Single Year uses an impressive 315g of Ume, The Choya Three Years 340g. Impressively, each bottle displays the average amount of Ume used in production. Masahiro Iida invites me to taste a Nando Ume. The flesh is firm, the taste tart, which helps create the delicious sweet and sour fusion in the end product. Later we visit the state-of-the-art bottling line, its perfect harmony evoking a peculiar beauty as hundreds upon hundreds of bottles are shuffled along a conveyor belt like little solders marching in tune. Such memories come flooding back as I write this article late into the night, precariously close to press-time on this special edition of The Moodie Davitt Magazine, a bottle of The Choya Extra Years alongside me on my desk. The alluring green bottle with seven small Nanko Ume inside offers a constant temptation to taste, though that will have to wait until the writing is done. Then and only then shall I reward myself with what I have discovered is a delectable combination of sweetness offset by fresh acidity and a voluptuous blend of exotic fruit. The Spirit of Japan in a bottle. |

Independent spirit

Three generations on, Choya remains firmly and profitably in family hands, despite being ringed by some of the biggest names in the international drinks business. What is the recipe to the company’s sustained success against such heavyweight rivals?

Three generations on, Choya remains firmly and profitably in family hands, despite being ringed by some of the biggest names in the international drinks business. What is the recipe to the company’s sustained success against such heavyweight rivals?

The answer, Kondo responds, lies in the relentless pursuit of excellence aligned with ambitious growth at home and abroad. “Right now we are the sixth-biggest liqueur company in the world, the ambition is to be top three in the future,” he says.

Growth in Western countries will be key to delivering that aim, with travel retail playing a pivotal role. Choya will go on test sale at Düsseldorf Airport later this year with Gebr. Heinemann, while the company’s continued presence at the TFWA shows in Cannes and Singapore underlines its commitment to the channel.

While popular with more mature consumers, Choya is also gaining strong traction with Gen Z and Millennials, drawn by the fresh, clean nature of its products and, perhaps most importantly, its strong sustainability credentials.

Choya uses 100% Nanko Ume (notable for being large in size, with thick flesh and high in organic acids) from the Kishu region, working with local Ume farmers researching and developing different solutions such as reducing pesticides, growing organic fruit, as well as creating optimal soil.

Choya is also innovating constantly, launching a popular zero-alcohol expression and becoming Japan’s biggest importer of agave syrup (a sweetener commercially produced from several species of agave) as it considers alternatives to sugar.

As we sip on a magnificently rich but balanced Choya Gold Edition, a mix of French brandy and 100% Nanko Ume with gold flakes, before heading into downtown Osaka for a farewell dinner, I ask Kondo for a concluding message to the travel retail community. He emphasises the brand’s popularity with women – over 60% of its overseas consumers, marginally under that in Japan – as testament to The Choya’s ability to attract travelling shoppers that other spirits brands do not.

I remind him of the spectacular success of Camus Josephine Pour Femme Cognac in the 1990s, a beautifully presented Cognac specifically designed to appeal to feminine tastes. He nods and adds: “Airports will be like the train stations of the future and so we have to be closer to all the casual travellers, and especially ladies. This is important not only for us but for all other categories.”

I remind him of the spectacular success of Camus Josephine Pour Femme Cognac in the 1990s, a beautifully presented Cognac specifically designed to appeal to feminine tastes. He nods and adds: “Airports will be like the train stations of the future and so we have to be closer to all the casual travellers, and especially ladies. This is important not only for us but for all other categories.”

Choya is putting its money where its mouth is, having opened an upscale dining bar in Tokyo’s plush Ginza district simply called The Choya Ginza Bar. “Some 80% of the guests are ladies,” says Kondo. “In Japan the name Choya is very related to ladies and we want to utilise this image overseas. I’m dreaming not only of Japan, but New York, London, Seoul and Shanghai as well.”

He hopes Choya can ride the globalisation of Japanese cuisine and form part of a Japanese wave. Such thinking underlines just how far the company has come since that bold diversification 64 years ago. How does Kondo feel about bearing the family standard well into its third generation? He reflects for a moment, then harks back to when he took over the company reins 15 years ago.

“Just after succeeding my seniors, our development was not good enough. Sales were rather flat,” he recalls. “In order to develop, we needed some innovations. So I sought the opinion from my employees and from the family members on how to create an innovative way of thinking.”

The resultant answers, manifested in a creative launch programme, allied to a ceaseless emphasis on product quality, social and family values, all underpinned by strong relationships with farmers, have served Choya well. With this proud company’s commitment to excellence and point of difference, the future surely looks bright. ✈

This article first appeared in The Moodie Davitt Magazine, click here for access.