“To understand what Amarone really represents you have to have been born here into a family of winegrowers, surrounded by these gentle hillsides. Amarone is more than just a wine or a technique – it’s a philosophy, an art, a life companion.” – Sandro Boscaini

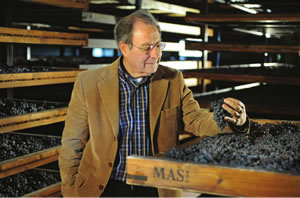

Meet “˜Mr Amarone’. Sandro Boscaini is a man among men in the wine industry – the President and sixth-generation owner of Masi Agricola, a winemaker which both embraces tradition and yet constantly challenges it.

He is a man who created a new and outstanding identity for a wine style, Amarone, which had for years languished as a mediocre, mainstream dry cousin of Valpolicella’s renowned sweet wine Recioto.

Boscaini’s story is wrapped up in a company whose enthralling history dates back to the beginning of the 18th century. It was then that the Boscaini family bought vineyards in the Vaio dei Masi (Masi Valley) in the heart of the Valpolicella region in Verona, Northern Italy.

|

“History is a heritage but not a straitjacket. In Piedmont they’ve been making Barolo for 300 years and they never think of doing anything different. We Veneti can’t stop ourselves studying processes that could lead to innovation.“ |

Sandro Boscaini President Masi Agricola |

To take lunch with Boscaini is to delve deep into that history and to discover the romance, wonder and future of wine. It is also a rare privilege: for here is an iconic figurehead for a newly iconic wine category, a man whose sense of purity, passion and perfection for the wines of his region transcends all commercial interests.

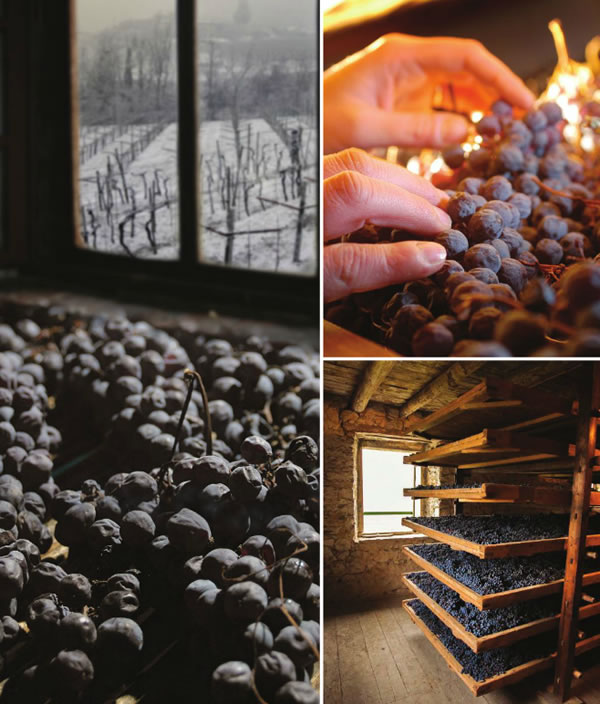

Today Masi is synonymous with Amarone and, in particular, with the Appassimento process – the intriguing practice of laying the harvested grapes out to dry on bamboo racks through the winter to concentrate the intensity, colour and aroma of the wines. The technique is used across the Masi Amarones and with “˜Supervenetian’ wines such as Campofiorin and Masianco.

Over a leisurely lunch (studded, needless to say, with superb Masi wines), I gained a fascinating insight into a man widely credited with the revival of the wines of the Venetian region – and particularly with the creation of a modern Amarone style.

Boscaini is simultaneously a traditionalist (deeply so) and a modernist. Under his leadership Masi has introduced a range of viticultural and vinicultural innovations that offer a contemporary interpretation of the ancient oenological traditions of the Venetian regions.

He’s even replanted some traditional but longabandoned grape varieties, and is making a series of unique, experimental wines with them. Over lunch, together with Pier Giuseppe Torresani (the man entrusted with driving the company’s travel retail presence) we drink a bottle of Masi Osar Oseleta, the Oseleta grape being a centuries-old Veronese variety rediscovered and replanted by Masi in the 1980s. Its exuberant mix of bold fruit, rich tannins and the trademark clean Masi finish more than live up to the company’s claim that Oseleta is a “jewel of our territory”.

|

“Times have moved on from when I put the grapes there and Mother Nature did what she wanted to. Today I help the Mother to give me the best results.” |

Asked about the convergence of traditionalism and modernism, Boscaini replies: “I don’t think that they are two antithetic words. I’m convinced that in an area like this, where the winemaking tradition goes back to Roman times with these local grape varieties and their unique winemaking methods, we really have to innovate, taking advantage of the modern possibilities and modern science – but keeping the soul of the past.

“That means keeping local varieties while looking to new and select clones. The same applies to viticulture, whether using Pergola [a traditional vine training system] or Guyot [a modern alternative]. We were among the first to use Guyot. Then there’s the winemaking. Yes, we can dry the grapes; but why do it as my grandfather did? We decided to do it in a contemporary manner – anything that gives more quality, because new technology and new equipment is welcome, provided it remains a natural drying process.”

“Times have moved on,” Boscaini says, “from when I put the grapes there and Mother Nature did what she wanted to. Today I help the Mother to give me the best results.”

Masi has driven similar changes in winemaking and fermentation. For example, it is one of a handful of winemakers in the world to have created its own yeast to aid the fermenting process. “It’s something that gives even more specific character to our wines,” Boscaini says.

|

“Only someone who has lived closely with the grapes and the wine can know what Amarone signifies – what it means to select the bunches for drying, to lay them out on cane trays, to stack them up in the drying lofts and keep them under constant observation, as you would a family member whose wellbeing is particularly dear to you.“ |

Sandro Boscaini, from “˜Amarone – The Making of an Italian Wine Phenomenon’ |

Boscaini’s relentless focus on the purity of his products rather than an obsession with profits is encapsulated by his mission to experiment with old grape varieties. After all, I suggest, he’s hardly likely to see any short-term economic return. The motivation, instead, is respect and love of tradition and history, combined with a desire to continually reinvent the art of winemaking.

“Yes, in a place like this with such a long tradition, you have to really find out everything,” says Boscaini with a smile. “Why did our father or grandfather do something in a particular way? Was it for some technical reason dating back hundreds of years? Or because it was really something that added quality? In many cases we find that there was a certain habit: repeating things because that’s the way they have always been.”

Masi has placed particular emphasis on the study of the Appassimento, discovering, for example, how well disposed the Corvina grape variety (which accounts for around 75% of the blend in the Masi Amarones) is to the process. The length of drying is as crucial as the technique, allowing the attack of “˜noble rot’ on the grapes, which is fundamental to explaining “this illusion of sweetness that makes Amarone so unique”, Boscaini explains.

|

“When you smell the Amarone, it’s like you’re smelling a sweet wine,” he says. “Instead, it’s actually a strong tannic wine with the bitterness at the end. But that’s one of the beauties of this wine, what makes it so different from any other. After this illusion of sweetness, where the wine is very open, it immediately becomes narrow, almost closed in a sharp way – then you discover a certain bitterness that invites you to drink again. It’s opposite to Bordeaux. Bordeaux is closed and then opens up.”

I know exactly what he’s referring to. Earlier that day we tasted the Mazzano Amarone della Valpolicella Classico 1988, a wine of true glory, its bouquet bursting with violets transforming into a long, lingering bitter cherry finish that I can still taste as I write this many weeks later. Boscaini likes to talk of making “˜modern wines with an ancient heart’. This great wine is the perfect embodiment of that philosophy.

Boscaini has never favoured the “˜celebrity or guru winemaker’ approach, preferring to focus relentlessly on a group style, nurtured through a technical committee (Gruppo Tecnico Masi). “I don’t want somebody who makes the wine based on their own style of winemaking or their own science,” he says. “So from the start I said I want wine that represents the style of the Masi company.

“This group really works as a team to deliver the best results of what Masi wants expressed in our wine. We want the touch and the character of tradition, but at the same time to be presenting contemporary wines.”

Sandro represents the sixth generation of the Boscaini family’s involvement in Masi, with his son Raffaele (in charge of marketing and co-ordination of the technical group) and daughter Alessandra (sales and administration) the seventh. One brother, Bruno, is Production and Plant Manager while another, Mario, has his own business but is still part of Masi and an adviser to the management.

|

“I have often been called Mr Amarone”¦ it’s a nickname I like, and am proud of, because it makes me feel like a miniature Marco Polo, intrigued by the discovery of new cultures; but also, aware of introducing something of my own culture as an Italian and more specifically as a Veneto, and indeed a Valpolicellese.“ |

Sandro Boscaini President Masi Agricola |

Those bloodlines run as deep and rich as a Masi Amarone yet, as our lunch draws to a close, Boscaini talks candidly of how, when he first started working with his father, he was not convinced of the future.

“Making wine here in Verona at the time [the mid-1970s] was really very hard,” he recalls. “Firstly, it was not paying off economically speaking. But more than that, there was a vulgarisation taking place with certain people making wine with sugar, which was something not morally or technically correct. At that time I was really very frustrated.”

At first he argued with his father that he should go into different work. But instead the Boscainis decided to return to their roots, in this case literally, focusing on the quality of the vineyards, buying them where certain wine giants were divesting land.

“We decided to rebuild our reputation and the quality of our grapes – starting with the right vineyards, the proper managing of those vineyards, and the wine we were making,” Boscaini recalls.

“So when everybody tried to attack the market giant from the bottom, I attacked from the top. I made the first modern-style Amarone. I made Campofiorin (lighter than an Amarone, deeper than a Valpolicella, made from re-fermenting the lighter wine on the skins of the Amarone). So it was something novel, something totally different. In the beginning it was quite shocking for the market; but I realised it was the right thing to do.

“We came out at Vinitaly in 1987 with an Amarone that was just three years old and everybody was still selling ’76, ’78. And it shocked the market. At first they said, “˜Masi’s selling too much, so they are forced to introduce wine that’s not ready.’ Later they realised that it was a real decision, and within a few years everybody went in the same direction.”

“I’m proud that I’m a viticulturist,” he says. “So today they’re my grapes making these wines, not the grapes that are given to me by other producers or wines that I bought through the cooperatives. This was the winning idea because it’s the contemporary idea. The wine must come from a vineyard that you know”¦ a vineyard that you touch, the soil that you touch.”

Underlining that commitment, Masi owns or controls through rental agreements each and every one of the hectares of vineyards from which it draws its great wine. “So we don’t buy any grapes from outside. It’s all about what we can inspect and control.”

Oddly, Masi’s quality credentials were given a boost by the biggest disaster ever to hit the Italian wine industry – the methyl alcohol scandal of 1986.

“Suddenly everybody was looking to producers who could prove that they knew and controlled the whole cycle from the vineyard to the table,” Boscaini says. “But it was almost impossible to export Italian wines, and we were forced to sell wines with a certificate. “But I remember what I did at the time. In England, for example, on a tour to see our customers, I said: “Look at my eyes: I know where my grapes come from. There is not a drop of wine from outside in my bottles. So I can guarantee with more than a piece of paper that there is no poison in my wines.”

As the old Latin adage has it, in vino veritas (in wine there is truth). At least if the wine (and the eyes) belong to Sandro Boscaini.

|

Sandro Boscaini and his team are driven by respect and love for tradition and history, combined with a desire to continually reinvent the art of winemaking |