Introduction: In this guest column, industry consultant Jack MacGowan, former ARI Chief Executive and DAA Chief Commercial Officer, highlights the challenges of airport tendering as the industry recovers from the pandemic. Noting the high volume of airport contracts that come up for bid in the next 18 months, he asks whether the best operators will prevail given chronic understaffing across airport commercial teams and concessionaire business development teams?

This feature first appeared in The Moodie Davitt Magazine for April. Click here for access (page 121).

For two years during COVID, airports paused tendering and extended incumbents’ contracts beyond the contract end date, writes Jack MacGowan. This worked as the few passengers that were flying were more concerned about their health and safety than the quality of retail store offerings.

Staying open during COVID wasn’t profitable for airports or operators but it was the right thing to do – allowing stressed passengers to relax and have a cup of coffee airside – a good example of partnerships improving the airport experience.

Now passengers are returning, and are largely over their acute safety concerns, and there are plenty of signs that they are not happy with the airport experience. Will the chaos of summer 2022 be repeated in summer 2023?

A recent Airport Dimensions’ survey published via The Moodie Davitt Report noted that while satisfaction was growing, there is a considerable dissatisfaction in the “middle of the journey”, which means that passengers are unhappy just when we want them to be spending.

Passengers are not happy to pay higher prices in neglected stores, or if they have to wait a long time to do the payment at a bar or restaurant. Airports know this and are preparing to tender commercial spaces so concessionaires will invest and lift the entire airport experience.

How many tenders will we see in the coming year?

Take the top 150 global airports, each with three tender cycles (duty free, F&B and other retail) and assuming an average seven-year contract term – in a normal year that would mean approximately 65 tenders.

By adding the next 150 smaller airports and the tail of small tenders needed where contract issues demand a separate Request for Proposal (RFP), the total number of tenders could be more than 200.

The bottom line is that in the coming 18 months, about 25% to 35% of commercial spaces in airports will be up for renewal. The number of tenders faced by concessionaires will double or triple, compared to what they would normally consider and bid for.

Two issues further complicate the situation. First, the profile of airport passengers has changed considerably and what passengers want is certainly not what we offer today.

Second, both airports and concessionaires have not invested ahead of recovery – supply lines are challenged, space allocation and concepts are not a fit for future passengers, and there is chronic understaffing.

Before COVID, when we had large and experienced business development teams, an operator might have considered roughly 30 tenders and bid on ten in a year, depending on attractiveness, availability of funds and timing.

Bigger companies could bid on more but no operator bids on every opportunity. From personal experience, I have the scars to prove that the easiest way to lose several important tenders that come up at the same time is to try bidding for them all.

However, during the pandemic, there were fewer tenders and the industry witnessed vast head office layoffs, and airport commercial teams and business development executives in concessionaires were ‘downsized’.

A temptation to cut corners

As a result, there is chronic understaffing and a dearth of experience across the industry.

Practically, the danger is as follows:

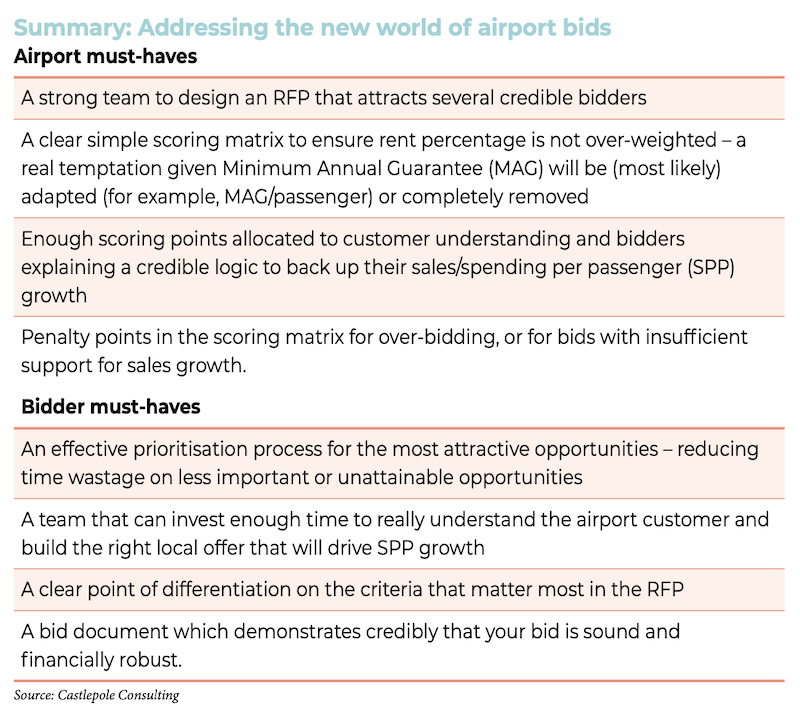

a) Instead of airports considering a revised RFP which reflects changing passenger spending patterns (for example, increased demand for F&B offers over retail) and bidder circumstances, and being tactically aware which other airports have RFPs out – they rush to publish the RFP and put bidders in a position where they must choose which opportunity to work on and bid for.

b) Instead of the concessionaire prioritising opportunities in the pipeline, they try to bid for everything and cover all opportunities with a superficial offer in a standardised bid document format.

c) As the understaffed concessionaire team tries to cope with the increased workload, they cannot properly understand the local customer and their tastes/needs, so they simply ‘cut and paste’ from an existing bid document.

d) As the airport commercial team are under pressure and understaffed, they focus on the simplest KPIs (for example, percentage for rent) at the expense of the more qualitative elements of the bid, such as customer understanding and localisation.

The disaster scenario takes shape when the airport team is unable to identify that the most generous bidder doesn’t understand the local airport customer profile, has cut corners and is bidding ‘blind’ with flawed logic supporting their promise to grow spend per passenger and increase profits.

When airports fail to identify blind bidding, it is likely to be sub-optimal for all, if not an unmitigated disaster, when reality catches up.

Focus, prioritise and plan

For concessionaires, doing more work on fewer bids will result in the best offer for passengers. It will also reduce the risk of over-bidding and ending up with energy sapping, loss-making contracts.

Similarly, airports need to focus on how they differentiate themselves and ensure the RFP is well thought through. It should be less about attracting a large number of bidders and more about ensuring that a small number of bidders are investing enough in genuinely understanding the passenger profile and local needs.

No matter how good we want to be, it is inevitable that some bidders will be tempted to cut corners and submit risky, poorly thought through bids. And particularly so if airports are issuing poorly designed RFPs and the commercial teams fail to spot blind bidding. ✈

Contact Jack MacGowan at jackmacgowan@castlepole.com

Contact Jack MacGowan at jackmacgowan@castlepole.com