17 April

17 April

Publisher’s Introduction: The New Deal was a series of initiatives during the Great Depression launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt which aimed to restore prosperity to an American society ravaged by the worst economic downturn in US history. Roosevelt took office in 1933 as the Great Depression, which began in 1929 and would not abate until the end of the 1930s, raged.

While the New Deal’s array of experimental projects and programmes, met with mixed success, the concept fundamentally changed the US Federal Government’s role within the US economy.

With the global aviation sector stricken by the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, is the airport ‘travel retail’ sector (including food & beverage and other services) in need of its own New Deal, and what might that look like? What are the contractual models that will lend the best chance of success for all stakeholders in the future – and help deliver the best possible consumer propositions?

The Trinity Initiative, launched today by The Moodie Davitt Report with the cooperation of a range of senior industry stakeholders and in association with leading international management consultancy Bain & Company, aims to identify a range of solutions. Bain & Company has provided its capabilities and resources as an industry service to ensure rapid progress can be made on a critical issue facing the aviation and travel retail sectors.

![]() It will take the form of public articles and debates (both via our media and at our virtual and, in time, physical events such as The Trinity Forum) and – more importantly – critical behind-the-scenes conversations with a range of industry leaders representing all stakeholder elements and other parties with the appropriate vision and complementary knowledge and skillsets.

It will take the form of public articles and debates (both via our media and at our virtual and, in time, physical events such as The Trinity Forum) and – more importantly – critical behind-the-scenes conversations with a range of industry leaders representing all stakeholder elements and other parties with the appropriate vision and complementary knowledge and skillsets.

How can airports best ensure the funding they require from non-aeronautical revenue sources? What is the best way to ensure a ‘win’ for the airports, while ensuring that they attract the necessary investment and expertise of quality commercial operators and their brand partners?

“The Trinity Initiative comes at a time when our channel is starved of the very oxygen that it has always been able to count on and always been underpinned by – passengers,” said The Moodie Davitt Report Founder & Chairman Martin Moodie.

| Announcing The Trinity Initiative Webinar Next week The Moodie Davitt Report will host two webinars (across different time zones) dedicated to The Trinity Initiative. These will feature Mauro Anastasi and Jack MacGowan discussing the Trinity Initiative and the Bain & Company airport presentation. Dates & times: *Friday 24 April 10.00 CET and 17.00 CET. To register your interest (please specify which session) please email Martin Moodie at Martin@MoodieDavittReport.com The meeting will be conducted by Zoom. Invitation details will be forwarded next week. Any industry stakeholder who would like to take part in a consultation discussion as part of The Trinity Initiative should contact Martin Moodie at Martin@MoodieDavittReport.com |

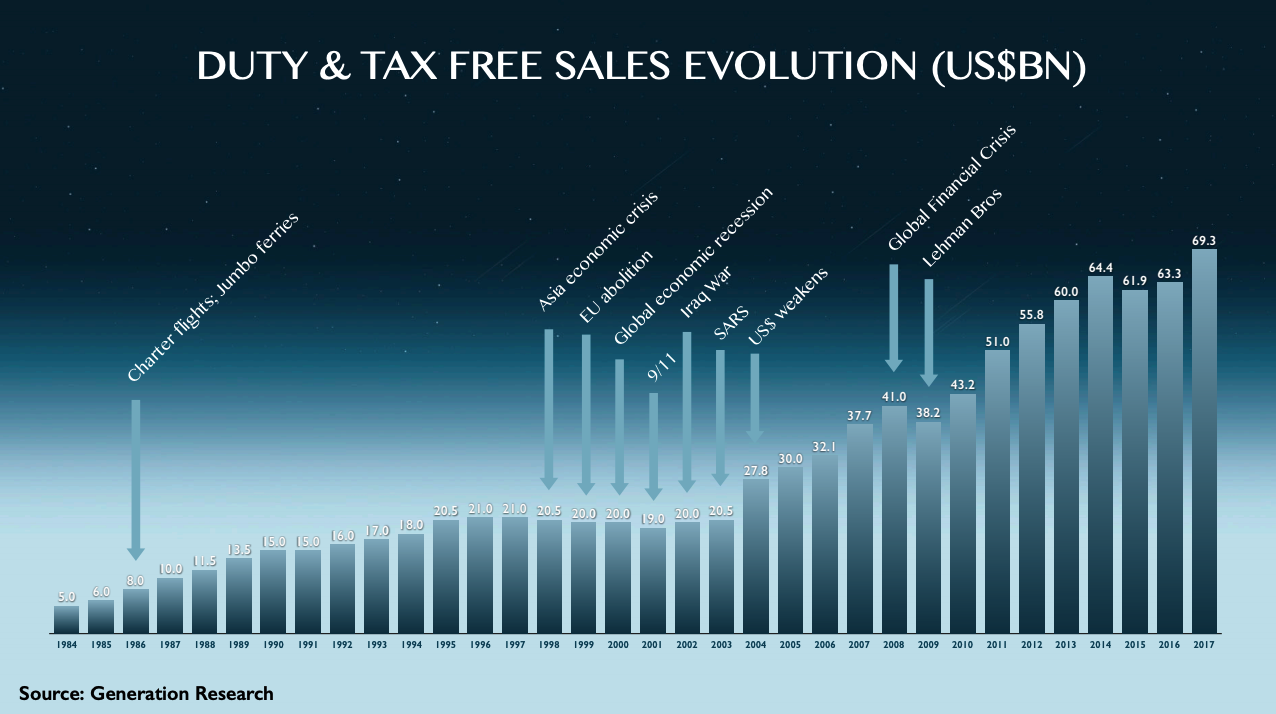

“That traveller base, which has risen exponentially over recent decades and was projected to continue doing so for many years to come, was the safety net that allowed the travel retail industry to flourish. That was despite a prevalent concession model that many have long felt provided an inequitable share of risk and reward.

“The devastation wreaked by COVID-19 means that in many countries at least the travel retail industry cannot return to such a model. Even if still able to, retailers in many countries will no longer be prepared to table high minimum guarantees, and brands will not be prepared to underwrite any that do. If that is the case, how can airports best ensure the funding they require from non-aeronautical revenue sources? What is the best way to ensure a ‘win’ for the airports, while ensuring that they attract the necessary investment and expertise of quality commercial operators and their brand partners? Those are the key questions that The Trinity Initiative seeks to answer.”

Airports simply cannot fund their operations through reliance on aeronautical revenues alone; commercial revenues have been pivotal to their ability to fund infrastructure and will be increasingly so in the future, especially with so many of the global airlines in distress.

The Trinity Initiative kicks off today with an extensive discussion paper produced by Mauro Anastasi, a Partner with Bain & Company Italy and Jack MacGowan, Director at Castlepole Consulting in Ireland and former CEO of Irish state-owned Aer Rianta International (2011-2018). Anastasi is an expert in Bain & Company’s Retail, Airlines & Transportation and Advanced Manufacturing & Services practices, with over 15 years of consulting experience across retail and aviation sectors within both Europe and the Middle East.

Over recent weeks, Anastasi and MacGowan have been working on a paper headed ‘COVID-19: A New World for Airports’ (made available to The Moodie Davitt Report readers on a complimentary basis via the link below]. It starts with these words, “Control what you can. Quickly. Start preparing for the ‘New World’.” In other words, fight the fires and then plan.

Much of this paper mirrors the aims of The Trinity Initiative. It seeks to scope what the ‘New Deal’ of airport retail will look like. And without question, there will need to be one. In that regard, we perhaps need to suspend references to travel retail’s historic resilience – not because that traditional wisdom is no longer true but because we are talking about an external crisis of a magnitude that the modern aviation era has never experienced.

The Trinity Initiative will be conducted in several phases.

- Next week The Moodie Davitt Report will host a webinar featuring Anastasi and MacGowan (details to follow soon).

- A consultation phase, which has already begun with key stakeholders across multiple sectors on an anonymous basis, will continue post the webinar for approximately two weeks. Specific questions and issues will be identified for deeper discussion with representatives from the industry Trinity. Finally – and no later than four to five weeks after the webinar, a White Paper will be produced.

- Afterwards, a periodic review will be established, involving players that wish to join. Thus The Trinity Initiative becomes not a one-off solution but an ongoing review mechanism that can be drawn on by industry stakeholders if necessary.

- Findings and recommendations will be discussed during the Virtual Symposium at The Moodie Davitt Virtual Travel Retail Expo in September.

“This is absolutely not like all the other crises,” says Bain & Company Italy Partner Mauro Anastasi. “Unfortunately we believe this will be the deepest recession that any of us around the globe has ever seen… with an impact on passenger traffic that will be much stronger and much longer lasting than anything we have seen, including SARS and so on. We believe it could be three to five years in terms of passenger traffic recovering to 2019 levels, especially for the long-haul leisure traffic that is the fundamental [element] of travel retail.

“We believe that will change travel retail forever in terms of the approach of travel retailers everywhere in the world… in their category mix and in their P&L structure. Travel retail will not disappear, but it will be a different game. That means that airports will need to significantly rethink their retail areas in terms of sizes, structures, store mix, brand mix category mix etc. Brands will also need to rethink their presence in the airport dramatically.”

Anastasi says that the traditional sector view of great resilience to and ability to bounce back rapidly from crisis, while still clung onto in many quarters within the airport and retailer community, does not hold true in the COVID-19 situation. “We cannot simply switch it all back on and go back to our normal life,” he says.

He also says the balance of industry relationships has shifted. “There are individual travel retailers who are probably the weakest link in the chain at the moment because their greatest asset – their airport contracts – have actually just become their greatest liability,” he says.

He also says the balance of industry relationships has shifted. “There are individual travel retailers who are probably the weakest link in the chain at the moment because their greatest asset – their airport contracts – have actually just become their greatest liability,” he says.

How so? “In a world where there is presently no real ability to do long-term planning on a) flight traffic, b) consumer and passenger behaviour as a consumer and as a shopper, a contract that is based on significant fixed minimum annual guarantees is a liability and not an asset anymore,” he explains.

“We strongly believe that in the future you will see a very different structure in terms of risk sharing between airports and travel retailers. I’m not sure we will see the kind of rent level minimum guarantees that we have seen in some tier-one airports in recent years.”

But while travel retailers’ greatest asset, their contract portfolio, may have been tarnished, it’s not all bad news, Anastasi reckons. Post-crisis, some travel retailers could even be in a better position because airports will be more open to risk sharing, he says. “There will probably be lower rent and a better sharing of risk with the airports – but with a lower overall business because passenger numbers will go down and most probably spending per pax will go down as well.

“But that kind of risk sharing will be down the line, a minimum of one year and probably more than that. The issue we now face is what happens between today and let’s say one or two years.”

That precise dilemma was exposed late last month at Incheon International Airport when preferred bidders Lotte Duty Free and The Shilla Duty Free opted not to take up their new Terminal 1 liquor & tobacco contracts under the current terms (underpinned by minimum guarantees). The big risk they saw was of losing a lot of money.

“Betting your company on a significant bid with significant minimum guarantees on unknown scenarios is something that no travel retailer today can afford to do – it’s simply too risky and too open-ended,” says Anastasi. “I don’t think there is any clear solution in the industry yet nor do I think there will only be one solution.”

Building a bridge between crisis and a return to normality

Anastasi foresees the need to have some kind of “bridge solution” for one to two years. “This is where the airport basically takes the bulk of the risk on pax and dollars per pax and gets a travel retailer to operate with a small/zero risk level just to do the basic job. Then, once the situation is a bit clearer, there will be new tenders with completely different conditions.

“The whole structure of airport commercial areas will have to be rethought. Some things will remain as is, but others will need to change. In such conditions you cannot have a [traditional] tender. A long-term contract obviously gives the travel retailer a number of rights in terms of space locations etc. And in the next one to two years, as an airport you need to be free to adapt your sales area to what you understand the consumer will want. The only thing we know is that it will be very different from today.

“Airports will need to improve significantly their customer understanding capability. It will be on their shoulders to understand how to respond to the consumer, while having someone taking very minimal risk assisting the retail operations. And then in the mid-term, new tenders will be generated that are adapted to a new world which by that point will be much more stabilised and clearer.”

Anastasi says that such moves actually represent an acceleration of trends that were already happening in the airport commercial revenues sector – airports taking increased responsibility for their travel retail operations (and having greater capability), which sometimes represent the biggest percentage of EBITDA.

Anastasi says that such moves actually represent an acceleration of trends that were already happening in the airport commercial revenues sector – airports taking increased responsibility for their travel retail operations (and having greater capability), which sometimes represent the biggest percentage of EBITDA.

These trends will dramatically accelerate, he reasons, and over the next two years the role of the travel retailers will become very different from today. And beyond that? “That’s a great question. For the retailer it will be more based on operations and less about taking risks. Extracting value from the passenger will be led more by airports.

“I guess it will also be a very polarised world. For sure this crisis will activate consolidation and probably also stimulate many small players. They could be local players that emerge from the ashes of existing larger players, because unfortunately it’s likely that at least in some locations certain travel retailers will have to abandon their contracts. In that situation, what you might have is local retailers coming in and taking over existing personnel and business and limiting their operations to one or two airport locations.

“But the dramatic difference that you will have is at the top-tier airports, which will have to be rebalanced somehow. Because I don’t see from an investor point of view how retailers will bid and take the risks that they take today.”

What happens to the MAG?

So what will develop in the short term as the sector emerges badly scarred by the crisis? What happens with current MAGs, for example, most of which (either by airport agreement or simply retailer refusal to pay) are not being paid as a result of the unprecedented collapse in passengers and revenue? There is no single answer, of course, but Anastasi believes there will be examples where the airport owner (single airport or group) will choose to activate any MAG guarantee that is in place.

“There are contracts with a bank guarantee that can be activated immediately. So clearly one short-term option is for the airport to say, ‘I activate the MAG.’ Let’s assume, say, it’s six months. So what I’m taking in 2020 [into my accounts] is six months of MAG. That is a much better multiple than what I can possibly get through any negotiation. Obviously when you have only 7,000 passengers, the airport will not get the equivalent of the MAG through percentage rents, not even half of it. It’s a trend of thinking that might seem unfair, but if an airport is trying to protect its short-term cash situation, it can simply push the button and get six months of MAG.”

Some airports may simply decide to do just that and be prepared to call someone in to run the retail operations on a zero risk base with a management contract or something similar, thus buying time to devise a long-term concession model, Anastasi says. “And frankly, talking to some airport investors, they understand perfectly that this is a short-term action, but they are also investors and have to report to LPs or institutions. How do they tell the company or institution that is putting in the money that they didn’t push the button… and didn’t take six months of MAG during such a dramatic crisis?

“The problem is obvious and it’s happening everywhere. You can sit down with the travel retailer and try to find a solution. But in a negotiation, you need to have something to give and something to get and today the travel retailer unfortunately doesn’t have much to give because the asset that is their contract is actually a liability.”

All the normal ‘fixes’ – additional capex by the retailer in return for an extended concession, for example, simply do not apply here. And by extending their contract, the retailer would simply be extending their pain.

Airports as critical infrastructure

Airports as critical infrastructure

Anastasi emphasises the fact that airports are not simply businesses but also critical strategic infrastructures. Many are state-owned, while others work on a concession basis with the state in some form. “So they have a responsibility to the state and to the community they serve that is about much more than making money.

“Many airports are asking correctly for state support. The problem of the government is that everybody’s asking for support. No government today has all the money for everybody that needs it. So, it’s a dramatic matter of high-level political choices – about who I support and who I cannot support.”

Jack MacGowan [former CEO of ARI] echoes that theme, emphasising an airport’s critical role and its strategic impact on the GDP of a city or country. Any subsidy is far more likely to be granted for, say, airline landing charges than for on-airport commercial services – despite the undoubted role that such activities play in funding airport investment and keeping travel prices down. In the Darwinist world of COVID-19, such choices will ultimately have to be made in some cases.

“Ultimately some airports cannot afford to care – even if the relationship (with their retailer) is wonderful or even if they think the retailer will do an outstanding job in the future,” he says. The message is painful – the survival of the airport will override the survival of the commercial operator every single time.”

MacGowan points out that most airport retail contracts involve parent guarantees, usually falling into two categories. The first is a bank guarantee – a letter of guarantee from the bank which is given to the airport and which they can trigger at their will. The second is often a performance guarantee. “In other words, no matter what happens, you need to keep your shops open from first flight to last flight and you need to continue to offer a service or something similar.”

While there are many variations on the financial model, in many cases the airport will have at least a month or perhaps even a quarter of rent in advance of the MAG rent, with the ability to cash the six-month bank guarantee in the case of default.

Surely the retailer can cite the force majeure clause in a contract (if it has one)? That is, an unforeseeable circumstance beyond the reasonable control of a party, that prevents it from fulfilling one or more obligations in a contract – typically wars, acts of terrorism, acts of god, or, in this case, a global pandemic.

Even that may not be enough to stop the airport cashing in the bank guarantee, MacGowan cautions. Some may simply choose to do so and then negotiate retrospectively, especially with cashflow such a critical need.

“Airports will not go bankrupt,” Anastasi adds. “So having cash today for one year and then even aiming to give it back in one year is a great option for an airport because basically it’s a loan. It’s a bank credit that today otherwise might be far from easy to obtain.”

Airport rethink of the commercial model

Airport rethink of the commercial model

Some airports have already come to the realisation that the new world of travel retail will be completely different from the previous one, Anastasi says. As mentioned, airports may prefer a more flexible arrangement than being locked into contracts which are inherently difficult to adjust.

Landside retail, increasingly the poor relation of airport commercial activities in recent years, may be an unexpected beneficiary of the almost certain need for airport medical screening, at least in the pre-vaccine phase of COVID-19. “That means that landside – something that we all thought was totally gone from a travel retail and commercial point of view – might actually come back. Because first you will queue for the test; then you will make the test; then you will wait ten minutes for the result; then you will you get the message on your app. And then you will head to the security filter. So you’re basically transferring a part of your time from airside to landside. That’s the kind of thing that might happen, though nobody really knows with enough precision if and how it will be.

“What will happen to food & beverage retail in airside if you need to be one metre from anybody else? Nobody has the answers, but I strongly believe that the airports will need the freedom to understand what is happening – to read the new consumer behaviours and adapt their retail conditions accordingly to this new world. You cannot do that with a traditional seven-year contact.”

[Click on the Podcast to hear Rick Blatstein, CEO of US airport F&B and retail specialist OTG talk recently about bringing “game-changing” checkout-free shopping to US airports at select CIBO Express Gourmet Market stores with the deployment of Amazon’s Just Walk Out technology — a world-first for airports.

[What would shopping look like if you could walk into a store (or F&B outlet), grab what you want and just go? Amazon has the answer. Expect more of the same in the post-COVID-19 airports of the future.]

Forced digital adoption

Anastasi and MacGowan also believe the COVID-19 learnings will accelerate airport retail’s omnichannel development. “The whole world has now gone through what I call forced ecommerce,” Anastasi comments. “We are all buying through ecommerce because while the grocery stores may be open, there is the queue factor; you cannot get out without a mask; or with only one person being allowed in at a time and so on. So everybody’s trying to move to ecommerce. This is a massive global trial and, as in any trial, a share of the people that have tried will stick to the new channel. How many, nobody knows, frankly.

“That means that all the travel retail players and airports will have to really accelerate their omnichannel development. That is not pure ecommerce, obviously but is about the whole link between digital and physical applied to airports. Very few players in the sector have really tried to invest in this way but it will become deeply relevant.”

Licence to kill – virus vs bomb

Licence to kill – virus vs bomb

“What humanity has discovered in the last couple of months is that while travelling, you can get a virus that can kill you,” says Anastasi. “This time it’s COVID-19; in five years it could be X, Y or Z but it still kills you. Whereas before, normal people thought while they are travelling that, ok, they might get a flu and have to spend a couple of days in their hotel room. Bad, but nothing dramatic. Now the world has just discovered that while you travel, you might get sick enough to die and not by going into some godforsaken place – we’re talking about some of the world’s mega cities.

“To me, that will change the way everybody looks at travel, especially leisure travel, because business is somehow a necessity. Obviously, if your travel is not necessary, and you have the option to go somewhere closer – maybe by car with your family – and you combine that with the largest and deepest recession in the modern era, then it’s not looking good.”

Anastasi contrasts this crisis with that faced by the travel and aviation sectors after 9/11. After that trauma, the industry reacted in a highly coordinated way with huge capex on security-related programmes to convince people that the risk of travelling was low. “There was tremendous investment in new technology, new processes and procedures, but the whole thing was a hugely coordinated effort by all players in the industry.

Anastasi contrasts this crisis with that faced by the travel and aviation sectors after 9/11. After that trauma, the industry reacted in a highly coordinated way with huge capex on security-related programmes to convince people that the risk of travelling was low. “There was tremendous investment in new technology, new processes and procedures, but the whole thing was a hugely coordinated effort by all players in the industry.

“It’s much more complex to identify a virus versus a bomb. And for now we only have the technology to identify the bombs. You will have airports trying to become as safe as possible – both into and out of the airport. That’s why it will be much more complex… and will require a full review of the value chain with all the major operators trying to ensure an end-to-end service that is kind of virus free.”

Does the likelihood of a COVID-19 vaccine in, say, a year, mitigate the need for longer-term structural change? “On one hand I agree, it’s not the right time to do long-term decisions,” Anastasi responds. “That’s why I’m envisioning a transition or a bridge period. Because, quite simply, we don’t know what we don’t know.

“How long will it take [to develop a vaccine] and is it even possible to think that you can really immunise against it? It’s a huge challenge… especially because I do believe that the risk of another virus will remain in the minds of consumers for a few years.”

[Contact details: Jack MacGowan, Castlepole Consulting: jackmacgowan@castlepole.com; Mauro Anastasi, Bain & Company Italy, Mauro.Anastasi@Bain.com]