Is Force Majeure the next must-have clause in travel retail concession agreements for the long-term benefit of both airports and travel retail operators? Ivo Favotto, a Sydney-based executive and company owner who has worked for all three stakeholders in the Trinity chain, examines the arguments.

Airport concession agreements have a long history of being written largely in favour of airports rather than concessionaires. This is not meant to be a pejorative statement or a criticism of any party to such an agreement. Rather, it simply reflects the economic reality of such agreements – more often than not there are more travel retail companies who want concessions than there are concessions available.

Airport concession agreements have a long history of being written largely in favour of airports rather than concessionaires. This is not meant to be a pejorative statement or a criticism of any party to such an agreement. Rather, it simply reflects the economic reality of such agreements – more often than not there are more travel retail companies who want concessions than there are concessions available.

This gives airports the economic power to include contractual conditions in concession agreements that transfer a larger degree of the risk to the concessionaire. In normal times, travel retailers are prepared to accept this transfer (by and large) in return for access to a valuable business opportunity.

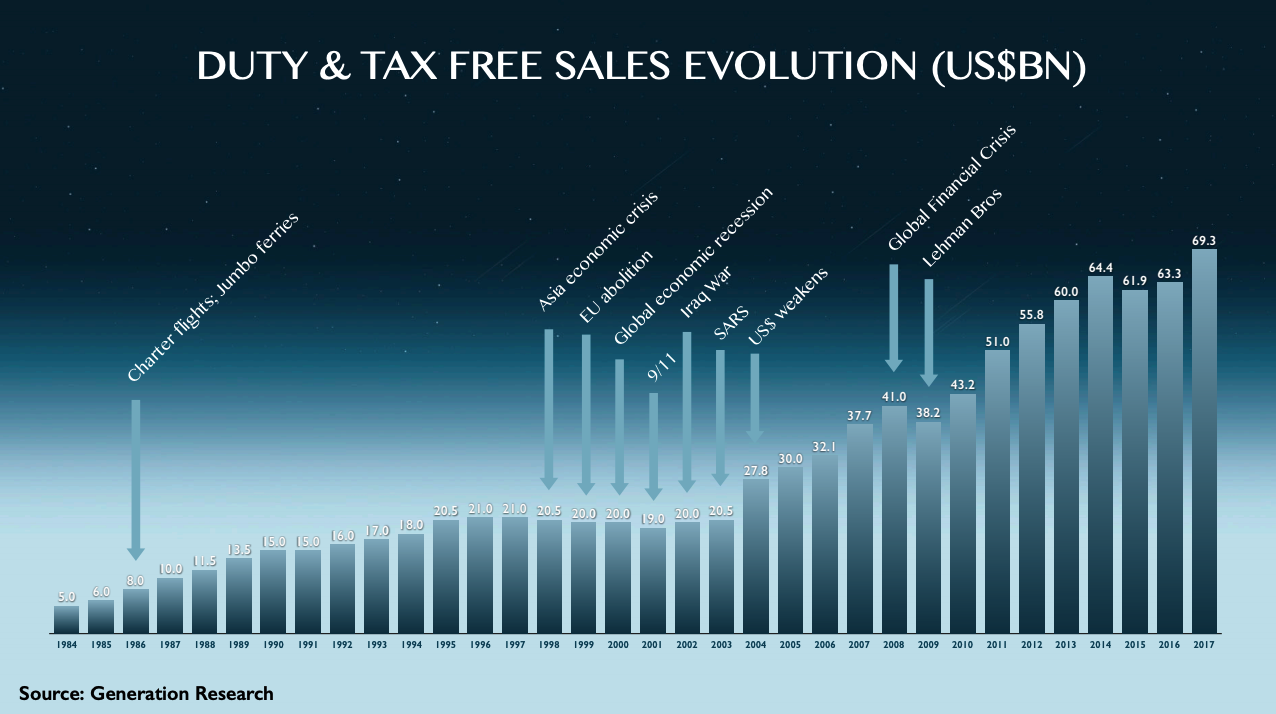

Notwithstanding the economic reality driving outcomes in airport concession agreements, there have been several examples where world events which have changed the context in which concession agreements operate. Those events have impacted the balance of risk and reward in airport concession agreements and COVID-19 may be the next one of these.

The first example was the response of some airports to the various (and in hindsight relatively minor) crises over the past few decades which have – typically temporarily – affected passenger volumes. These include wars, terrorism and financial downturns. Some airports responded to these external events by agreeing to tie Minimum Annual Guarantees (MAGs) to passenger numbers.

While such arrangements may provide some relief to retailers during periods of passenger number decline, they also bring more risk and significant pressure on retailers during periods of rapid passenger growth. Other airports responded by allowing the introduction of ‘Armageddon’ clauses that provide for pro-rata reductions in MAGs once passenger volumes fall by more than X% (typically 40-50%) over a 12-month period. Such clauses are struck in the knowledge that sustained falls in passenger volumes of material magnitude are very rare, but nevertheless they provide a degree of comfort to the operator.

The second example is the wave of anti-tobacco regulations that hit duty free a decade or so ago. This external change to the industry has now made Material-Adverse-Change (MAC) clauses much more common – and in some jurisdictions universal. These days, most duty free concession agreements have a MAC clause which states that if the business is impacted by changes in government regulation (typically in the country where the concession is held but sometimes in other countries as well), then there will be some abatement of rent.

An event of the current profound magnitude renders the lack of a force majeure clause in a concession agreement almost meaningless – i.e. if the consequences of adhering to a concession agreement are greater than the consequences of not adhering to that agreement then the concession agreement becomes less relevant.

Of course, proving that the MAC is the only thing impacting sales and that the retailer has done all that it can to mitigate its own losses are another matter. And of course, the mechanisms, quantum of abatement and calculation methodologies all differ contract to contract, some being more generous and less onerous than others.

Which brings us to what may become the third example of where world events force a change in airport concession agreements – the force majeure clause. A force majeure event is an unforeseeable circumstance beyond the reasonable control of a party, one not caused by the party, that prevents that party from fulfilling one or more obligations in a contract – typically wars, acts of terrorism, acts of god, or, of course, pandemics.

Usually, the force majeure event must make performance of the contract impossible, not simply more difficult or more expensive (although making a contract much more difficult and expensive may make it impossible – e.g. insolvency).

A force majeure clause must be specified in the concession agreement. If no force majeure clause exists, then the occurrence of such an event will likely leave the affected party liable for any resulting agreement failure, even if the failure is beyond its reasonable control (unless the counter party is willing to give ground).

A force majeure clause can take many forms. It is up to the parties to agree what is force majeure and how it will apply between them if such an event occurs. Typically, a force majeure clause allows an affected party to avoid liability for a breach of contract, with the affected contract obligations being suspended for a short, specified period of time, and with the ability for one or both parties to terminate the contract if the force majeure event continues beyond that specified period of time.

The vast majority of duty free and travel retail concession agreements currently do not contain force majeure clauses. It is anticipated however that COVID-19 may change that.

Since the realisation dawned on us that the COVID-19 crisis was a global pandemic, we’ve heard the line repeatedly that “it will change the world as we know it”. In travel retail, it is anticipated that this means – at the very least – that inclusion of force majeure clauses will be vigorously sought by retailers.

Having the imprint of the world’s largest global force majeure event since 1939-1945 burned into their psyche, no travel retail executive will be able to convince their internal management committee or Board to sign a concession agreement in the future without one. Hence force majeure clauses are likely to become standard in airport concession agreements.

The airport industry’s best interests are served when there is a large volume of healthy competition for concessions. This allows airports to be price setters rather than price takers, given that there are multiple credible responders to tenders and calls for expression of interest.

What the current COVID-19 crisis is teaching the travel retail sector is that an event of the current profound magnitude renders the lack of a force majeure clause in a concession agreement almost meaningless – i.e. if the consequences of adhering to a concession agreement are greater than the consequences of not adhering to that agreement then the concession agreement becomes less relevant.

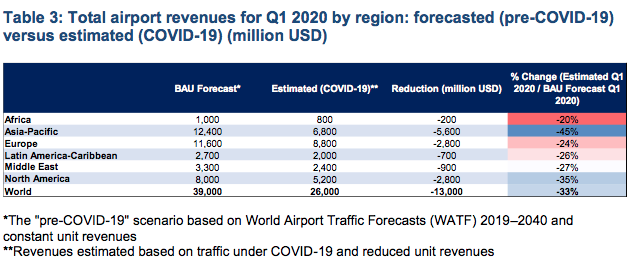

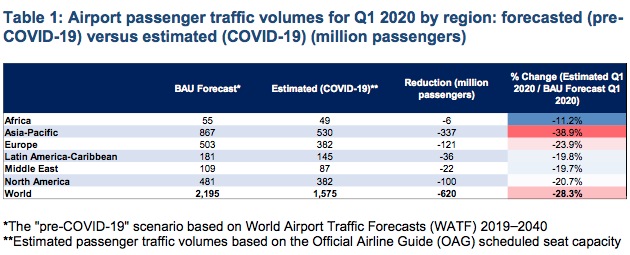

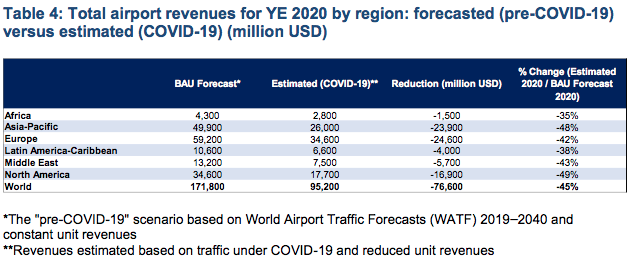

The current COVID-19 crisis – where many airports are experiencing material reductions in passenger volumes (-70% and sometimes over -90%) and where many terminals and stores are closed – is having a catastrophic impact on travel retailers and food & beverage operators. Many are facing a very real crisis of solvency where they are not able to meet their debts as and when they fall due. Any business where revenue is materially impaired yet continues to face costs such as rent and staffing is likely to face a crisis of solvency.

And so, as counter-intuitive as it may sound, force majeure clauses may actually – in some circumstances – be in the best long-term interest of airports.

The airport industry’s best interests are served when there is a large volume of healthy competition for concessions. This allows airports to be price setters rather than price takers, given that there are multiple credible responders to tenders and calls for expression of interest. This means that airports need travel retailers to be there, in financial health and vigorously competing for concessions when the COVID-19 crisis is over.

The longer the COVID-19 crisis lasts, the bigger the risk that airports face as an industry that some important retailers may not make it through. At this stage, it seems that traffic volumes will take quite some time to recover, varying by country and by region. According to the global industry association for airports, Airports Council International (ACI), it may be two years (at least) before global traffic volumes recover to 2019 levels (Source: ACI World webinar by Patrick Lucas, Director Economics, April 2020).

Could an airport go to the market now to find a new operator? Who would want to take on a new concession at a time of such deep global uncertainty without the airport taking all the risk?

According to ACI, this is likely to be driven by three key factors: the depth of economic recession anticipated; an asynchronous global recovery (different countries recovering at different rates prohibiting a global re-opening of borders) and potential behaviour change (businesses switching to digital meeting platforms).

Concerns about the very survival of some travel retailers and their ability to come through the other side of this crisis ready to take advantage of any bounce back in passenger volumes is why – force majeure clause or no force majeure clause – some airports to their credit have already made some abatements to rents (see earlier reports in The Moodie Davitt Report about how airports such as Singapore, Hong Kong and Bangkok have gotten on the front foot of the COVID-19 crisis).

While other airports might not come to the negotiating table so willingly, come they probably will because the longer the crisis goes the cost and risk of having an operator fail may be greater than the cost of a rent abatement.

The cost and risk of having an operator fail is real. Could an airport go to the market now to find a new operator? Who would want to take on a new concession at a time of such deep global uncertainty without the airport taking all the risk? And what sort of price/value would an airport get for its concession in the current environment? And what about the transition costs and risks for both the airport and the retailer?

Could a new retailer find staff in the current environment? New retailers would be unable to travel to inspect sites. The supply pipeline for fixtures is disrupted. Supply pipelines for stock also potentially face disruptions.

Could a new retailer find staff in the current environment? New retailers would be unable to travel to inspect sites. The supply pipeline for fixtures is disrupted. Supply pipelines for stock also potentially face disruptions.

Which takes us back to force majeure clauses in concession agreements. Better to have a known and understood set of actions and consequences for a force majeure event than the frantic and emotionally charged renegotiations (best-case scenario) or tense stand-offs (worst case) currently going on. Better to have operators with a clear pathway to surviving a major downturn and being ready to trade on the other side.

While theoretically the lack of a force majeure clause may appear to de-risk returns for airports, what the COVID-19 crisis has illustrated is that the financial consequences of a major crisis are unavoidable – regardless of what’s in the contract – for all parties.

For airports, there may be great risk in the uncertainty of how the current crisis will play out and some (particularly smaller, regional airports) may find the crisis will limit their ability to attract competitive fields for tenders in the years to come. With no road map in the concession agreement that determines how to manage a force majeure event, there may be greater costs for airports in the uncertainty – and the prospect of lawyers being the biggest winners.

Individual agreements aside, on a global scale, without calm heads prevailing, the certainty provided by force majeure events may help travel retail operators to survive and in the long term preserve a high degree of competition in the sector – which is in the long term interest of all airports.

If a significant proportion of travel retail operators do not survive from this unprecedented crisis, the travel retail world (passengers, suppliers, airports and operators) will be the poorer for it.

Note: The Moodie Davitt Report welcomes your feedback on this article and on the whole subject of how concession contracts should be structured in the future. You can add your comments (anonymous if preferred) below or by writing in confidence to Martin@MoodieDavittReport.com

*About Ivo Favotto

Ivo Favotto has a long and distinguished record in the airport and travel retail sectors. A trained economist, he entered the airports/infrastructure sector with Australia’s Federal Airports Corporation in 1992 as GM – Planning & Economics.

He later built a highly successful international airports/infrastructure consulting practice, working with three firms – Bach Consulting, Arthur Andersen and URS Corp – and advising many of the world’s leading airports, governments and investors in the areas of retail planning, master planning and privatisation/transaction support.

In 1998 he established the market-leading Airport Retail Study, selling it to Moodie International so he could join The Nuance Group (now owned by Dufry) as Executive Vice President – Strategy & Business Development in Zürich. He later returned to his native Australia as Director – Sydney Airport before being named Executive General Manager of Duty Free & Luxury, Pacific for Lagardère Travel Retail.

He has now formed The Mercurius Group, a Sydney-based consultancy focused on industry research, consultancy and benchmarking studies. The company also assumes responsibility for revamping and relaunching The Airport Commercial Revenues Study (ACRS), which Ivo founded (as The Airport Retail Study) and sold to Moodie International in 2007 as part of an informal alliance between Mercurius and The Moodie Davitt Report.

He has now formed The Mercurius Group, a Sydney-based consultancy focused on industry research, consultancy and benchmarking studies. The company also assumes responsibility for revamping and relaunching The Airport Commercial Revenues Study (ACRS), which Ivo founded (as The Airport Retail Study) and sold to Moodie International in 2007 as part of an informal alliance between Mercurius and The Moodie Davitt Report.

Contact: Tel: +61 423 564 057; E-mail: ifavotto@themercuriusgroup.com; Website:www.themercuriusgroup.com